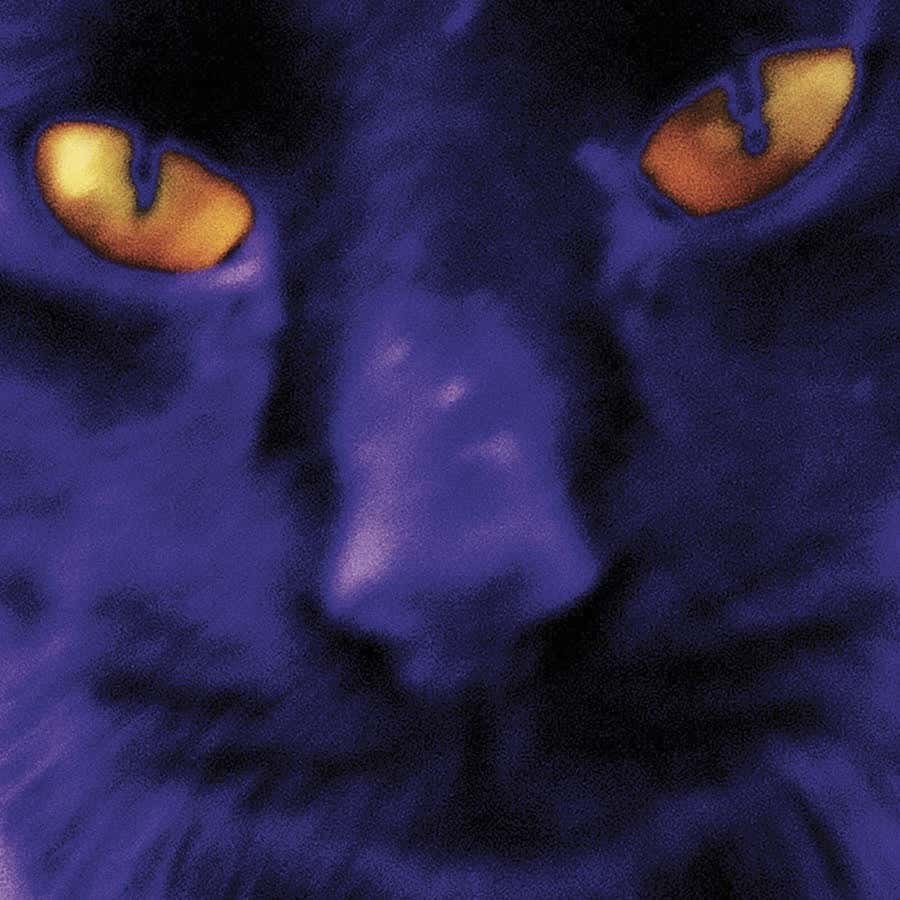

Black Cats & Blue Highways

Dunedin songwriter and musician David Kilgour’s new album Bobbie’s a girl is out September 20. He spoke to Richard Langston.

Is there a story behind that title Bobbie’s a girl?

For the last session of recording we had the house full of people and we’d just got Bobbie the cat, a stray that turned up on our doorstep, quite sick actually. I called her Bobbie after Bobbie Gentry cos I’d been listening to a lot of Bobbie Gentry that week. Tony (De raad, guitar player) kept saying ‘…he’s outside..’ and I said, ‘Man, Bobbie’s a girl!’ and it became a tag for a while and I said, ‘Hey, hey we’ve got a title for the album buddy!’. It’s one of the closest relationships I’ve ever had with an animal… this cat’s awesome.

You had the same band for this record?

Yeah but because we’re scattered (drummer Taane Tokona lives up north, Tony De raad now lives in States) there’d be a gap of six months between sessions and when we’d get together we’d only record for two nights cos it turns into work after two nights. We got about a third of the album in one or two nights in the first session four years ago. We were in no rush at all. We finished it about 18 months ago so we sat on it for a long time which I’ve never really done before. But I’m always interested to see if we still liked it after four years.

You wrote it over a long period, it didn’t all come in a rush…?

I’ve been pretty dry over the last ten years. It’s not been easy put it that way. But I’m in no rush, what’s the pressure y’know.

But in that time you’ve put out quite a few records…the two Sam Hunt albums …Left by Soft (2011) …End Times (2014)

We did put out two albums in one 12 month-period, the Sam Hunt one (The 9th) and End Times Undone. We pretty much toured them too so we were busy there. It was quite surprising, we talked about that Sam album for probably three years and suddenly out of the blue Sam just wrote and said ‘Ok, I’m ready let’s go’.

End Times seemed a bit of a break-through album for you…

Small biccies but it sold in The States, as many as Feather in the Engine. They’re the best-selling albums though I don’t know if you call it selling any more! Mojo magazine in England put it in their top 40 for the year which was surprising, they said it sounded like The Byrds were rehearsing downstairs, and I thought yeah, I’ll take that (laughs).

I think many people who’ve followed you over the years would regard Feather and End Times as among the high points…

Really? We didn’t tour End Times here so we didn’t really get that much feedback, I spent all my energy on America for that one. What’s sustained me for in the last few years has been that American audience and Merge. They’re such great record company people, actually I wouldn’t even call them record company people. They’re just great people. In the next few years there’s going to be more Clean stuff in the archive that will be released.

I love the song “Comin’ On” off End Times, it’s a song where you seem almost mesmerised by the joy of being in the moment creating a song…

It was a magic moment when we came up with that. I like that one. We were just about to go into the studio for the first time and I didn’t have much material. The day before I went out on the porch and just sat down and bang! I got the riff and the basic melody. That doesn’t happen very often but it’s great when it does, it’s like ‘yeah, I still got it’ (laughs). That album’s got some weird bits but it is kinda sparkly.

I imagine your mood was very different when you started to write and record the new album…

The first session had a certain mood, it wasn’t really on purpose but I thought ‘fuck, I like this’, really melancholy and very simple. We all dug it and we’re just going to mine it and see how much I can get out of that mood.

“It’s really hard to verbalise grief – it’s new territory for me.”

At that time I imagine you were preoccupied with Peter Gutteridge (who’d been in The Chills, The Clean, The Great Unwashed and Snapper) and his passing (in 2014) – a great friend you’d known since school…

Most of the album was a reaction to Peter’s death. I’m not really one to run to the guitar when something major happens, not sure why, maybe it seems a bit too obvious. I didn’t write anything for about 10 months, I sat in a daze really. I was amazed how writing about it helped. It’s an obvious thing to do, of course it’s going to help… puts it in black and white. You can focus on it, and then walk away from it. It’s like a long exhale, a breathing out.

What was it about Peter? What attracted you to him when you first met?

We definitely hit it off straight away, within a couple of weeks I was out at his house in Portobello and that’s where we came up with the idea to start the band (The Clean).

Did you share a vision at that time of how music should be?

Not really. I think for him it was a brand new idea, he’d mucked around with things and he drew a little bit. I knew he liked Gustav Klimt and he had a Mahavishnu Orchestra album which I thought, mmm I’ll accept that for now but you might have to move on from that buddy! I can’t believe I was so snotty at 16. To be fair he did also have the first Roxy Music album. But he was not really immersed in rock’n’roll like Hamish (David’s brother) and I were.

Peter was quite brave and cheeky and I was quite shy. He’d go places I wouldn’t and I’d just tag along and try and pull him back (laughs).

Roy Colbert (music writer & owner of Records Records in Dunedin) once said to me teachers regarded Peter as the boy who questioned everything…

We had a student-teacher for history called George Kay and I think he called Peter one of the most difficult students he’d ever had to deal with, Peter put up a good argument. He was in the debating team, I think I was too actually (laughs). Peter liked to debate (laughs).

I don’t remember him being troublesome at school, I hardly saw him actually, the year of the 6th form he just didn’t go and at the end of the year they accredited him. I wanted to kill him! ‘How did you do that!?’ Peter just walked through fire sometimes (laughs).

Like many human beings he was something of a paradox – he had these various sides to him – he could be amazingly sweet and write songs like ‘Universe of Love’ and ‘Planet Phrom’ but he was into guns and war…

But that was much later on, that side of Peter was much further on down the track, the Peter I met was a charming intelligent creative, really open guy, loved people, really social. The darkness was later. I was living with him when he came up with the songs that we later recorded with the Great Unwashed (“Born in the Wrong Time”, “Can’t Find Water”, “Boat with no Ocean”) and he was just on fire. He chipped away at it, he was a pretty good bass player in a primitive sort of way with the early Clean, and he started to chip away at the guitar still quite primitive but the stuff he was doing was great.

People like to go on about the guns but y’know Peter loved to play on that, ‘I’m a big tough guy ha ha ha’, he liked to play with his image, he was a good bull-shitter (laughs). It was a bit of a pose and a laugh really, he only ever had air pistols. I’m sure he went to some dark places and had trouble here and there. It’s that obsession, William Burroughs and all that. That was part of it – he was a multi-layered character.

“…It’s a conversation between two dead people and someone who’s alive – it’s a just a mood piece.”

I remember when he died and you posted that Martin Rev song Mari and said something like, ‘We loved this one eh Pete’…

We loved that stuff, it’s a stunning wee EP. I remember really loving the second Suicide album but I don’t think anyone was obsessing about it. Peter almost stumbled into that when he got a 4-track portastudio and started getting better on the six-string guitar then got a fuzz box, and I thought ok! Then the first Snapper show with Stephen (David’s band at the time) it was instantly great. It was a revelation, ‘Snapper and the Ocean’ wow, too good. Years and years, he just nailed it down to that one note. He almost devolved, he’d honed it to the point he became a lesser player in some ways, it’s what he wanted and it worked for him.

He was always going on about the sizzle, get the vibrations sizzling man (laughs). He was trying to put himself to sleep I think, meditate into the other zone, when it was really working you’d see him start nodding off (laughs). We all use music as medicine anyway and for Peter that was part of it, trying to calm himself down. He had a really hyperactive mind.

He never started stopped creating, he was always doing something at his house. He’s lived within a kilometre of our place for 30 years or something. We’ve always kept in contact Peter and I, we’ve always had that connection even when we fell out we’d always get back together eventually. The last couple of years of his life he cleaned himself up health wise and the light came on and it came on really bright. He was still creating wonderful stuff, I remember one day I went over and he said listen to this and he had a lead plugged into a delay pedal that was plugged into an amp and he just picked up the lead and shorted it and it just made this gorgeous sound and he started singing to it and I was like ‘wow!’

After he died that ten months I didn’t do anything much about it but I thought maybe if I write about it might make me feel better. It actually worked, it was great. Any time some bleak or melancholy stuff came along I’d go into the studio and whack it down and that’s pretty much what happened.

At one point we thought let’s make a double album cos we were mounting a lot of stuff, there were over 20 tracks we liked. Looking back now I realise I pulled out all the melancholy tracks (laughs). There’s another album there which is interesting.

The single “Smokes You Right Out” there’s melancholy but there’s sweetness to it..

That was the first one. That’s Peter, that’s saying goodbye, that’s letting him go. It’s really hard to verbalise grief, it’s new territory for me. Peter’s death and then my mother’s death not long after, like wow! There’s hardly any lyrics on the album, there might be 20 lines. Grief is just indescribable y’know. The statement is the album, it’s not really made to talk about really.

In some ways it’s a conversation between two dead people and someone who’s alive – it’s just a mood piece. I think if it does anything it might calm you down a bit which is not a bad thing in this world (laughs).

As a lyricist you’re often quite open and impressionistic…as much using your voice as an instrument…

I’ve been trying to hone that more and more in the last few albums, I think Nick Bollinger recently said it’s almost like I’m not writing a song but there is a song there. The thought of sitting down with the lyrics in front of me and the intro and the chorus and the middle eight and quirky wee thing with a turnaround thing I just can’t go there anymore. I really love to be able to write as close as possible to the recording even if that means putting everyone under pressure and they don’t know what the song is …all that stuff (laughs). I’ve got a really good relationship with the band now so it’s a joy really.

I remember your mother at the gig in Christchurch when The Clean reformed in 1988 and she said, with a big smile on her face, ‘oh, I do love creative people!’

She did, she really did, and she didn’t mind the freaks either. The stranger ones we took home were the most fascinating to her really.

She was musical herself…

She played piano and did a little bit of theatre when we lived in Ranfurly. She was quite a cool artist, a good drawer, she was made to be a creative person but it wasn’t really the right time for women artists. She really encouraged us with art and a little bit with me in music.

Hamish posted a picture of your mum standing with family in front of a car back in the ‘60s …a very cool picture…

Fuck, I love that photograph. That’s how her family the Aulds dressed. They’d dress up and go and visit the cousins. They look like they’re in a country band and have just flown in from Nashville or something. My mum’s brother, Uncle Jack, was just a total dandy.

Jack and family while visiting their farm in Marlborough in 1964.

You’ve been making music and writing songs for a long time – I make this your 11th album – and one of the people who inspired you and who you worked with, Chris Knox, has been virtually side-lined by a stroke …you must miss his creative energy…

Yes, of course you miss his voice, yeah, and I’m sure he does too. It’s sad he lives at the other end of the country or I’d see a hell of a lot more of him. He’s there but it’s a different Chris. He’s still manages to perform – the strength of the guy, the power, the will. He’s brave Chris, he always was, gutsy as fuck.

And many of the musicians who started in that era in Dunedin are still making music…still writing songs…

The lifers are yeah. Graeme Downes (The Verlaines) has worked hard, he’s got a pretty full on job, he’s still managed to make music. Shayne (Carter) has been a lifer, Martin (Phillipps), Hamish, Bob (Scott), Chris Heazlewood…the list goes on. It’s lovely some of us have stuck at it. I used to be disappointed when I was younger when people pulled away but looking back I can’t blame them. It’s a mental life to get into, it’s not easy financially.

We had so much luck and we pretty much all had success. It all happened pretty quickly so we were encouraged early on. That was one thing I thought was missing from The Chills’ doco… the sheer joy of making music at that time, it was wonderful. It was kinda astonishing and magic. Everyone was on the dole, we were all writing quite good songs, and suddenly boom!

I’ve had a really charmed life. I haven’t worked for about 30 years. As long as I’ve got a car and a house and surfboard a piano and a few guitars and I get to travel every couple of years I’m pretty much a happy guy.

And you paint of course…

That helps pay the bills and I enjoy it… been painting a bit more than usual actually. It’s a good thing to do in winter (laughs). I’ve been having a good break from music but I am ready to do something. Touring will be good, I haven’t done a live show for four years or so. I’m ready to do something different, something new, whatever that may be. I’ll do it till I drop, I don’t know if it will always be in the public eye, but I’m just going to keep on going.

Purchase the album here – https://www.mergerecords.com/bobbies-a-girl

David Kilgour on tour:

Oct 24 Queenstown, NZ – Sherwood

Oct 25 Dunedin, NZ – The Cook

Oct 26 Christchurch, NZ – Blue Smoke

Oct 31 Wellington, NZ – San Fran

Nov 02 Auckland, NZ – Whammy Bar

Nov 03 Auckland, NZ – Whammy Bar

Recent Comments