The Zen of Noise

By Richard Langston

The formidable and internationally-appreciated noise trio, Dead C, is releasing its 34th album, Unknowns. Bruce Russell spoke to Richard Langston about his on-going excitment making spontaneous noise with fellow band members Micheal Morley and Robbie Yeats – and digging for old 45s.

A new album Bruce – how did that come about?

It’s quite a story. Last October on Labour weekend I went down to Dunedin, Robbie has the use of a cottage at Aramoana, right out on the spit, and he said come down, we’ll fire up the bbq for two or three days and do a bunch of recording. We did and that was great, the place has a walk in chiller for the beer so it was very nicely set up. We recorded a lot of stuff, a couple of albums worth, but most of it was on a digital multi-track recorder and when Michael transfered the files there was one of those problems that happens. We lost everything.

But in the room we also had a couple of those hand-held zoom stereo recorders and we still had those. They had really weird bounces of sound because of where they were in the room and there were large amounts of stuff we couldn’t use. The record’s a collage of the bits we managed to salvage from the zoom recordings. Michael’s added vocals to most of the tracks and we’ve created our first ever 12” EP, 15 minutes a side. We’ve never done one and it’s the classic ‘80s NZ format. I’m pretty excited about that and the material sounds a bit different because of the way it was put together, there’s a bit more post-production.

Ironically, there’s two records coming out as we had some money from previous royalties to fund a European tour that was not possible and we’re using that to do a 7” 33, the other classic 80s format, and it’s got five things we’re calling songs. Michael’s edited them togther into two side-long chunks one of which is called two songs and the other’s called three songs. None of it kinda makes sense until you hear it (laughs).

Three songs…the first time I’ve heard that title since the Tall Dwarfs…

Yes, that’s the other reference. Nicely spotted. We’re doing about 300 to sell as merchandise for if and when we do any other shows, and we’ll make it available on Bandcamp. I’m quite excited about having something that’s easier to transport than a 12” record. One thing that’s killing touring for us is taking these fricken huge boxes of LPs, ah do we have to take them?, yes we do! (laughs).

Do you have any idea of what you were going to do when you started recording at Aramoana?

No, we never do.

One of your many collaborators, Alastair Galbraith, describes the moment you switch on the machine and start recording as being in the moment and like jumping off into the sea…

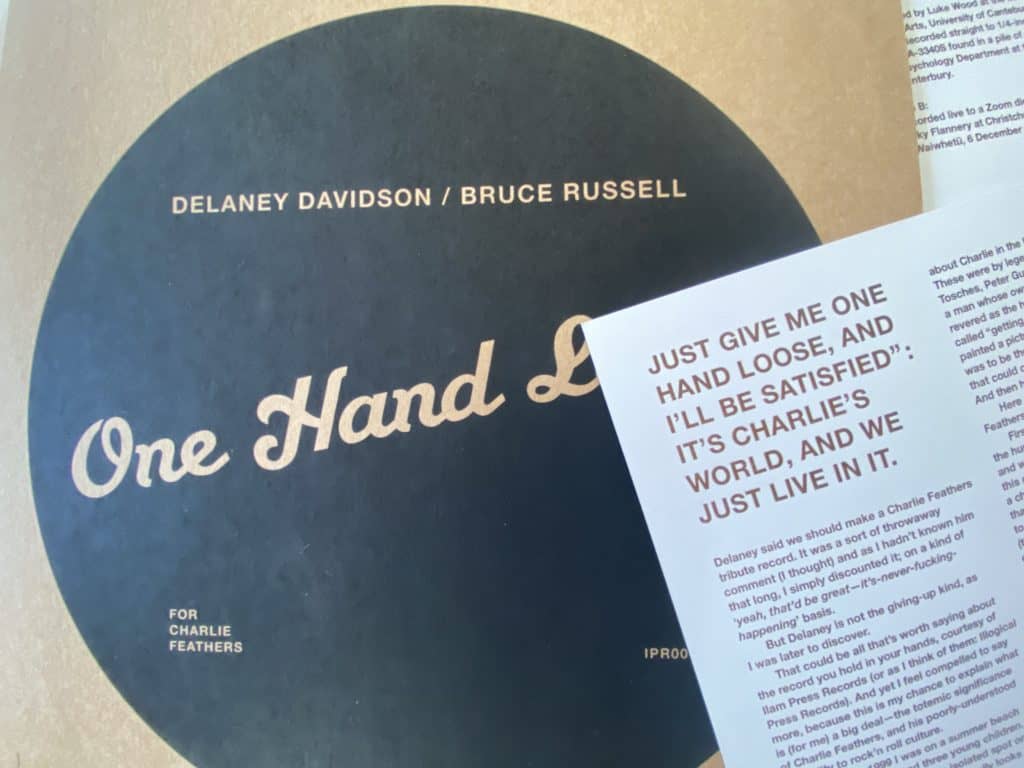

That’s probably fair. I resolutely refuse to prepare anything or rehearse. When I collaborate with new people – I did that record with Delaney Davidson for instance – he realised that’s the experience that I would give him, that I would just turn up on the day and then we see what happens. I find it a really productive way to work and it saves so much time.

I think that’s a great record, and gives even the casual listener a good introduction to what you do…you’ve got the reference of a traditional songwriter like Charlie Feathers who provided the starting point and you just make a mess of him in a good way…

Fucking everything up is pretty much my strong suit! Actually the most listenable record I’ve ever made is probably the Visceral Realists record I did with Luke Wood. It’s the most musical sounding and it was done the same way as the Delaney Davidson one on a Teac four-track. It’s got some keyboard stuff on it and a more subdued vibe and for whatever reason it came across as really nice.

All the rhythm tracks are constructed from the run-off grooves of old ‘60s 45s. I chose records from my collection that had interesting rhythms when the needle gets to the end …chick ah dah bok …chick ah dah bok…chick ah dah bok…I’d have a DJ set up where I’d have two run off grooves playing similtaneously and slightly manipulate them till they got into a good groove and recorded those and made three minute segments and then we overdubbed over the top of those.

We were trying to produce something in short order. When I start playing and I think I’ve got half an hour it can take ten or fifteen minutes to really turn into something but if you’ve only got three minutes you’re really on your game. It does produce a different result even though the method is the same.

Are they almost songs Bruce?

Sort of…

Which brings to mind something you’ve said in a previous interview which I think is another clue to what you’ve been doing these past 30 years …you said, ‘too many people think of sound as a way to present songs, I think sound is fundamental and songs are not…’

That’s what I think, yes. You’ve got to remember that when we started back in the mid-80s that was the heyday of the songs and you had bands like The Verlaines – and one third of our band was The Verlaines (drummer Robbie Yeats) – and The Verlaines were all about the song. We were pushing against something that was the prevalent approach. We decided early on we were going to do everything the opposite way. We just wanted to see what would happen and that was playing to our strengths. Why would we just be incompetent at something everyone else was doing when we could be spectacular at doing something nobody else was doing.

I remember when Graeme Hill introduced you for your first television appearance. He had this gleeful look of someone who can hardly believe he’s got you on the tele…

It’s the look of a 12 year old letting off fire crackers in church.

I remember thinking at the time something like, ‘Bruce is just winding everybody up, he loves to provoke people’, but I watch it now and I think it’s really good…intense, wild, good…

Thank you. The thing about that, and it took a lot of people a long time to believe this, we are actually really good at doing what we do because we’ve been doing it for 30 years, just the three of us. Whether you like what we do or not, after a period of time we are actually going to develop an ability to do the thing. I’m really proud of the fact that we are exceedingly professional. We’re a band who can get on a plane and fly for 30 hours, drive for six hours, and go on stage with no sound check and deliver a killer show.

When you’re playing with Robbie and Micheal, what is going on in your mind?

“The first year of playing with the Dead C I was convinced we were going to get bottled, someone would stand up and say, ‘You people! This is Bullshit! ‘You (pointing at me) you can’t play that thing what the fuck are you doing?!“

The difficult part of what I do is learning not to over-think it. I’ve always been not able to play the guitar, I was born not being able to play the guitar! What was difficult was retaining the clarity, the simplicity of vision of I’m going to play the guitar but I’m not going to worry about playing it. I’m just going to use it, I’m going to see what happens when I do things with it. As soon as I start to worry about how I was playing I became very self-conscious and that made it very difficult.

The first year of playing with the Dead C I was convinced we were going to get bottled, someone would stand up and say, ‘You people! This is Bullshit! ‘You (pointing at me) you can’t play that thing what the fuck are you doing?!’ And what surprised me was that never happened, but I was always ready for it to happen.

It took a lot of psychic training to get myself to the point where I didn’t think about that, and then I had to train myself when not to listen to the others because if you listen to them too much when you’re playing then you lose track. Now I only listen to myself, I just point at the nearest foldback and say I just want my guitar through that so loudly that it will feed back when I’m standing over here. I’ll hear the drums but I don’t need to hear Michael cos it works when we don’t listen to each other. My best current description of my guitar playing is a mix of Tai Chi and carpentry.

That’s a great description, and you’ve made a hell of a lot of noise over the years…

Yes, we’ve been running for 34 years and we’ve been doing an album a year on average. To be honest when I tell people how many records I’ve made I don’t know if they believe me (laughs). Personally I’ve made 75 albums, not just albums that I appear on but where I’m playing on the whole thing. If you include where I’ve made appearances on other peoples’ records it’s probably 80 or 90. That’s the virtue of not preparing.

But you’re committed Bruce and I think it takes committment to listen to your records, by that I mean they aren’t to be taken or listened to casually…

(Laughs) yeah, I get that. On all levels it takes committment (laughs). Listening to any records I’ve made, particularly the Dead C ones, it does take committment but the joy of the Dead C is it’s the unstable combination of three different things. If the stuff I do on my own has a weakness it’s that there’s too much of me and some days you don’t want to listen to just me, but with a Dead C record there are moments where Robbie does something, oh that almost sounded like music! And Michael will moan narcoleptically, oh that could be singing-ish! (laughs).

On the subject of committment, I have a memory of someone calling you an enabler – someone who gets things done and who helps others get things done – and I remember back in the mid-80s in Dunedin you not only wrote for my fanzine Garage, and enlightened me about bands I wasn’t so aware of, you also came around and stapled it together, a small thing, but I’ve always remembered that…

Ah yes, the stapling party! I do remember doing that.

Was it a party, I just remember the two of us grovelling on the floor with this large stapler…

That’s what I call a stapling party (laughs). There was a lot of stapling!

There was, it was Garage 5 i think and we were doing something like 1200 copies by then…

I like doing things with my hands, I’m an inveterate DIYer. I’m doing a rainwater irrigation system at the moment for relaxation. But running a record label was about making things, Xpressway and Corpus Hermeticum, I spent incredible numbers of hours folding covers, putting things together. Honestly, Corpus Hermeticum I folded something like 20,000 CD covers.

You’ve always had intent Bruce, you have very particular tastes and there’s band you’ve always advocated for, and I was astonished to see that intent once when I went record hunting with you…you were digging in old dusty singles bins where most people fear to go…

That’s an interesting point. Last week I went to Penny Lane records cos I was feeling stressed, and looking at shitty old 45s relaxes me. Almost immediately I found Surfin Bird by The Trashmen, and I thought this is why I do this, this is so exciting. For the last couple of years I’ve become quite obsessive about finding these old 45s. What attracted me to it was it was an affordable way to buy old records cos second hand LPs are now all 20 to 30 bucks.

You can pick up 45s for next to nothing.

It casts a light on one of my other obsessions which is recorded sound. Going right back to hearing Tally Ho by The Clean, that’s a funny sounding record and I’m not sure I like that but why I didn’t like Tally Ho when I first heard it was because it didn’t sound like records on the radio. And that’s because it was ‘poorly recorded’.

But I’ve really developed an interest in understanding how recorded sound mediates our relationship with music cos rock music is really about records. There’s a really interesting book by a guy called Theodore Gracyk – Rhythm and Noise: An Aesthetic of Rock – where he argues that rock music is about records, it’s not about songs, it’s not about performances, it’s about recordings and that’s a position I’m in sympathy with.

A big part of the Dead C’s career has been fucking with fidelity, and our records have a particular sound and it’s very carefully chosen, it’s what we like but it’s not what people are expecting. What I realised about 45s is, and this is the joy of them, we’ve all heard Surfin Bird on numerous compilations but the rock archeologist in me wants to know, what did Surfin Bird sound like when it was made in 1963?

Surfin Bird was pressed in NZ but the plates, the metal parts that were used to press the records, they were shipped from America to here and they were cut at the time from the master. The record I got for nothing the other day is literally no-steps removed from that process, it’s a record that was pressed in NZ in 1963 from a plate made from the master tape in Amercia, so suddenly there’s nothing between you and what it should sound like other than a bit of surface noise, and I’m good with that.

An illustration of the value of this is I’ve got two copies of Friday on My Mind by The Easybeats, one was the 1965 NZ pressing and one’s a 1973 reissue. They sound completely different because in the ‘70s they recut the thing and they put a bit of reverb on it and tried to make it sound like a 1970s record should sound, and it’s fucked up. That example alone confirms to me why I’m interested in hearing the originals.

What I’m also really really listening to is the quality of the sound, and so you hear something like Let’s Dance by Chris Montez or Tallahassee Lassie by Freddie Canon and you hear the bass drum and that was the first time a big drum sound had been used in a pop record and then two years later you hear Have I the Right by the Honeycombs as recorded by Joe Meek, and again the rhythm is people stamping on a wooden stair case, and when you know that and listen to the record you can really hear it and I just find that really exciting cos I’m interested in sound.

This is why you have earned a doctorate in sound… drilling right down into it…

“My advice to someone seeking to understand the recorded works of the Dead C is they should track down the original 45 of Let’s Dance from 1961 and play it at brain-melting volume, and then they’ll understand much better.”

Absolutely. There are remarkably few people apart from studio technicians and backroom boffins who are interested in these things, and there are remarkabley few artists who really seem preoccupied or knowledgable about these things and I want to caste a light on that.

In a weird way the career of the Dead C is the practical experience for me that came out of that process that’s led me to a philosophical position on sound and that philosophical position is producing new knowledge, and as an academic new knowledge is what we’re all about. I’m trying despertately to find the time to write the book that will come out of the doctorate to share the ideas cos I want other people to build on them. It’s hard to find the time even though I don’t spend any time rehearsing (laughs).

My advice to someone seeking to understand the recorded works of the Dead C is they should track down the original 45 of Let’s Dance from 1961 and play it at brain-melting volume, and then they’ll understand much better.

On the subject of sound, when Lou Reed died you wrote a piece for Wire magazine in which you said, the guitar solo in ‘I Heard Her Call My Name’ gave you persmission to do what you do…can you expand on that?

Yeah, again this is sort of about sonic archeology. The career that the Velvet Underground had when they existed was almost insignificant but their subsequent career since about 1974 when their legacy began to be rethought, it’s been a really interesting process of uncovering what they really did because we only knew what they did in the studio as there were so few workable bootlegs, but gradually more and more live recordings have become available.

I used to read a lot of American fanzines and I recall one based in Ohio called Black to Comm in the late 80s reprinted an interview with Lou Reed where he talked about guitar playing. It was only a couple of paragraphs but it stuck with me because Lou was trying to do stuff with the guitar that he thought was important and that involved taking guitar playing away from widdly-diddly tricky changes and finger picking expertise. He was trying to do with the guitar what Cecil Taylor had done playing the piano with his elbows, and all the free-jazz guys like Albert Ayler had done to break down technique, Ornette Coleman, y’know the harmolodic theory where he basically takes music and just chucks it out and says I’m going to play the saxophone and let’s see what happens, and Lou Reed had tried to do that with the guitar but on record there’s almost none of it.

But the break in ‘I Heard Her Call My Name’ is a really good example, I don’t know if it’s got any notes, it’s just a blurt. It doesn’t go for very long but it makes no i sense at all but it’s incredibly exciting. It takes the song into an entirely different dimension.

Then that guy finds the acetate of the Banana album sessions in a flea market in New York and it’s the first sessions and the album as it was originally conceived by Warhol and the Velvet Underground before record labels were involved.

It’s got a version of European Son which has an extra 1 minute 40 seconds at the beginning and this was actually edited out. You can tell when you listen to the released version and the acetate version, you can hear where they did a razor cut on the master and they just chopped it out. It’s another bit of this guitar playing, just this mad screaming blurt, it’s incredibly exciting but it’s been cut out of history. Lou felt by the time he got to the end of the Velvet Underground he didn’t want to play guitar any more. ln the early 70s, particularly around the time of Sally Can’t Dance, he wasn’t playing guitar live, he would just sing because he said no-one wants to hear me play guitar cos I tried doing that and they shat on me so I’m not going to do it anymore, fuck you.

The Lou Reed that fascinates me is the one the wanted to do with the guitar what Cecil Taylor did with the piano. It did inspire me, that and hearing Rudolph Grey playing on a 45 that was sent for review to Alley Oop (Dunedin-based faznine). Rudolph Grey on this record which is called Implosion 73 is playing with Rashid Ali the drummer who played with Coltrane on Interstellar Space, and when I heard that I thought Rashid Ali is playing drums with a maniac who is just making this noise with a guitar. This was in about 1991 when I was already finding my way towards this and when I heard that that was the other part of it. I’m going to do that. It was not something that anyone in Dunedin really wanted to hear.

I just want to change tack slightly and talk about the aesthetics of packaging. The Dead C records and the other records, cassettes, and CDs you’ve been associated with they’re always artfully done and are nice things to hold and look at … such as the Le Jazz Non compilation…the quality of the cardboard and printing…it’s a thing…even though it’s on a format many regard as disposable…the CD…

Interestingly I’m waiting Richard, for the CD to come back, I reckon it’s got to be another year or two before CDs suddenly develop the cache that cassettes got five years ago. I never thought the casette would come back, I was naive, now I know better. I have hundreds of CDs from the 90s cos CDs was my business and it is a great format. I was on a crusade – and it’s nice of you to notice – it was an effort to make the CD a more aesthetically pleasing format, there’s no reason it shouldn’t be. It’s a bit small let’s face it, but leaving that aside there is plenty you can do with the CD.

On another tangent, I always think you come up with great titles for the Dead C records, my favourite is Vain, Erudite and Stupid for the CD of the band’s selected works…

Yeah (laughs) that’s a goody. Those words in the Max Harris song lyrics are actually from a poem by Ern Malley who was really a couple of traditional poets who hated modern poetry and did a prank on Max Harris (then co-editor of the Australian literary journal Angry Penguins) by writing all this shit and calling it the poems of Ern Malley. When we were going through the process of compiling the 20th anniversary selected works of the Dead C there was no other title that it could be given.

When we listen to humans making sounds we generally look to them to tell us a story, to produce melody, or evoke feeling. Is what you do purely intellectual?

No, absolutely not.

It has an emotional quotient then?

Yes, to me it’s very visceral. I’ve certainly heard many sound compositions that read well on paper, oh conceptually I see what they did there, that’s a really good idea but fuck it’s boring to listen to. There’s a lots of people working in this area in an intellectual sense but they seem not to have any understanding of the drama and emotion involved. My point is that sound outside of music can also stimulate emotions and I’m interested in assembling sounds that are interesting and make you feel something.

When I’m playing the guitar and it’s going well – it doesn’t always go well – I get excited, I’m pretty juiced up about it. The first time the Dead C ever played together it was so exciting we were all absolutely ecstatically excited by what we were doing. I can distinctly remember literally dropping my guitar and running around inside Chippendale House running in circles kinda squawking, it was just that great. Excitment is just another emotion.

Recent Comments